What is it about Glastonbury's location which makes it so muddy?

Enable it in your browser or download Flash Player here.

Sorry, you need Flash to play this.

Video caption This is why it's often so muddy at Glastonbury

It's June, it's raining and it's Glastonbury Festival, so, inevitably, every news site in the UK is posting video of fans trudging through sludge.

We're not going to lie - it's nice to feel smug sitting in a dry office, on a chair, cropping photos of people looking muddy on day one.

But let's face it, this isn't the first time - and it won't be the last - that Glastonbury turns a bit, well, feral.

But why does it always look so much worse than any other UK festival?

Newsbeat has turned to science to get the answers.

More related stories

Woman in the crowd at Glastonbury

Glasto essentials you don't know you need

Festival-goers arrive for the Glastonbury Festival

Glastonbury revellers 'in 12-hour queue'

Weather

"This time of the year we get a lot of rainfall off the Atlantic," he says.

"It comes in these short, sharp bursts."

These heavy showers cause the ground to get waterlogged.

Girl wearing a mac by some tents

"Last month we had 134% of the normal rainfall," says Andrew McKenzie, a hydrogeologist from the British Geological Survey.

"That happens quite a lot, every two, three or four years. So far this month, and we're only two-thirds of the way through, we've had 190% of the normal rainfall, so that is actually quite exceptional.

"Glastonbury is prone to flooding when it's very wet and it has been extremely wet."

Geology

People walking through mud with their luggage

For flooding and mud you've clearly got to have wet weather.

But the Somerset soil also plays a crucial role in creating that unique Glastonbury squelch.

The soil is clay-based, explains Dr Kenneth Loades, a soil physicist from The James Hutton Institute.

"The trouble with clay is it's made up of very, very fine particles."

He adds: "Soil in a field has holes - that's where the water goes into and also where there's air. When it rains, these holes fill up with water, which makes it go into a horrible squishy mess."

Woman wearing a hat made of a rain cloud

The make-up of the ground also explains why it takes a long time for the quagmires to clear up.

"The whole underlying structure, underneath the farm, is clay and muds, so there's nowhere for the water to go," explains Andrew.

Grass

Two days ago the festival site looked green and lush.

"Grass is really useful because it does help reduce the amount of mud. The roots of the plant are within the soil and they hold the soil together," says Kenneth.

"Even when it's a sea of mud, it still has an element of positivity. Those roots are still there.

"It could be deceptive because you can't see the grass but I can assure you, it's still having a beneficial effect."

Geography

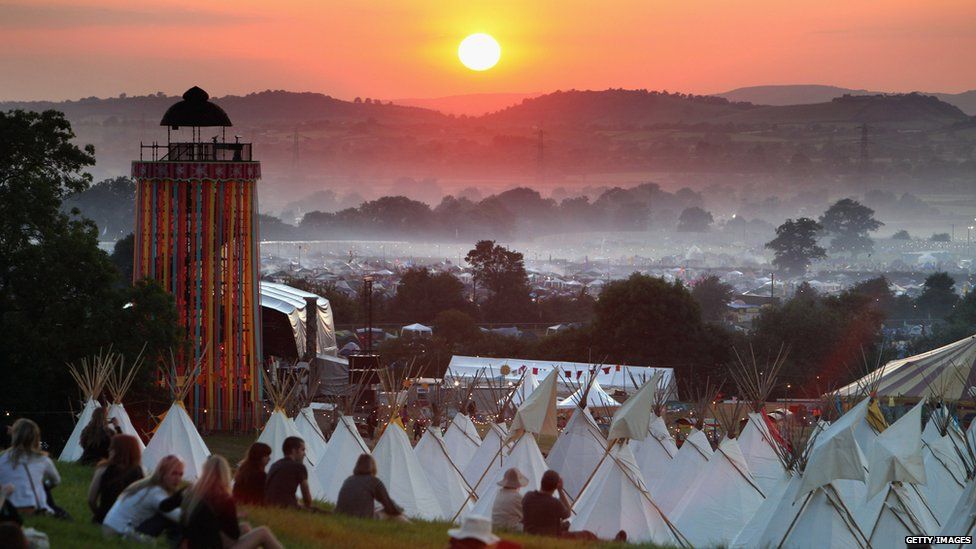

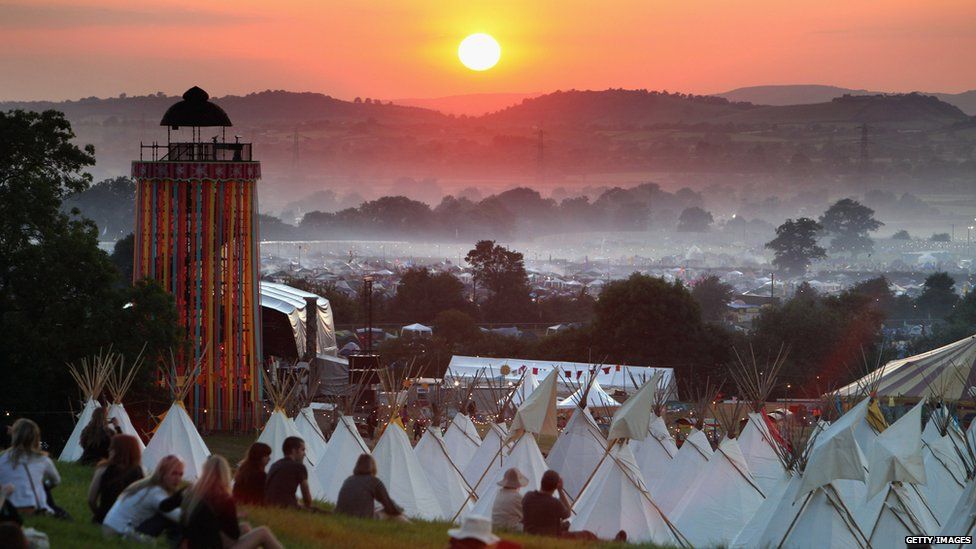

View of Glastonbury from the top of a hill

Glastonbury is also based in a valley.

"Water is always going to flow down hill," says Andrew.

"Because the ground is so impermeable, by which I mean the water can't soak into it, it means that any rainfall that falls on the ground is going to flow to the lower parts of the site.

"All the hillsides around Worthy Farm contribute extra water, in addition to the rain that actually falls on the festival site itself."

Anyone who's been to the festival before knows that it's the campsites higher up the hills that tend to survive the longest in the wet weather.

Population

People dragging a bag through the mud

About 175,000 people go to Glastonbury - that's roughly equivalent to a town the size of Ipswich, Wigan or Oxford.

"The physical action of people's feet, churning over, compacts the mud and removes some of the structure that's naturally in the soil," says Andrew.

"If you imagine you've got 20cm of soil - there's a lot of water in that.

"If you then walk a few hundred people across that piece of soil, you're crushing the structure down and squeezing the water out, in the way that you might squeeze water out of a sponge."

Enable it in your browser or download Flash Player here.

Sorry, you need Flash to play this.

Video caption This is why it's often so muddy at Glastonbury

It's June, it's raining and it's Glastonbury Festival, so, inevitably, every news site in the UK is posting video of fans trudging through sludge.

We're not going to lie - it's nice to feel smug sitting in a dry office, on a chair, cropping photos of people looking muddy on day one.

But let's face it, this isn't the first time - and it won't be the last - that Glastonbury turns a bit, well, feral.

But why does it always look so much worse than any other UK festival?

Newsbeat has turned to science to get the answers.

More related stories

Woman in the crowd at Glastonbury

Glasto essentials you don't know you need

Festival-goers arrive for the Glastonbury Festival

Glastonbury revellers 'in 12-hour queue'

Weather

- READ MORE

US psychologists claim social media 'increases loneliness'

South Korea's new President Moon Jae-in has been sworn in, vowing to address the economy and relations with the North in his first speech as president.

Everyone wants to run for US president in 2020

"This time of the year we get a lot of rainfall off the Atlantic," he says.

"It comes in these short, sharp bursts."

These heavy showers cause the ground to get waterlogged.

Girl wearing a mac by some tents

"Last month we had 134% of the normal rainfall," says Andrew McKenzie, a hydrogeologist from the British Geological Survey.

"That happens quite a lot, every two, three or four years. So far this month, and we're only two-thirds of the way through, we've had 190% of the normal rainfall, so that is actually quite exceptional.

"Glastonbury is prone to flooding when it's very wet and it has been extremely wet."

Geology

People walking through mud with their luggage

For flooding and mud you've clearly got to have wet weather.

But the Somerset soil also plays a crucial role in creating that unique Glastonbury squelch.

The soil is clay-based, explains Dr Kenneth Loades, a soil physicist from The James Hutton Institute.

"The trouble with clay is it's made up of very, very fine particles."

He adds: "Soil in a field has holes - that's where the water goes into and also where there's air. When it rains, these holes fill up with water, which makes it go into a horrible squishy mess."

Woman wearing a hat made of a rain cloud

The make-up of the ground also explains why it takes a long time for the quagmires to clear up.

"The whole underlying structure, underneath the farm, is clay and muds, so there's nowhere for the water to go," explains Andrew.

Grass

Two days ago the festival site looked green and lush.

"Grass is really useful because it does help reduce the amount of mud. The roots of the plant are within the soil and they hold the soil together," says Kenneth.

"Even when it's a sea of mud, it still has an element of positivity. Those roots are still there.

"It could be deceptive because you can't see the grass but I can assure you, it's still having a beneficial effect."

Geography

View of Glastonbury from the top of a hill

Glastonbury is also based in a valley.

"Water is always going to flow down hill," says Andrew.

"Because the ground is so impermeable, by which I mean the water can't soak into it, it means that any rainfall that falls on the ground is going to flow to the lower parts of the site.

"All the hillsides around Worthy Farm contribute extra water, in addition to the rain that actually falls on the festival site itself."

Anyone who's been to the festival before knows that it's the campsites higher up the hills that tend to survive the longest in the wet weather.

Population

People dragging a bag through the mud

About 175,000 people go to Glastonbury - that's roughly equivalent to a town the size of Ipswich, Wigan or Oxford.

"The physical action of people's feet, churning over, compacts the mud and removes some of the structure that's naturally in the soil," says Andrew.

"If you imagine you've got 20cm of soil - there's a lot of water in that.

"If you then walk a few hundred people across that piece of soil, you're crushing the structure down and squeezing the water out, in the way that you might squeeze water out of a sponge."

No comments:

Post a Comment